President Obama’s DHS secretary, Jeh Johnson, said that 1,000 illegal entries a day overwhelms the system. The Southwest border averaged 3,000 arrests a day in January.

The surge is so big that it has overwhelmed Mexican smugglers, who are now “requiring their customers to wear numbered, colored, and labeled wristbands to denote payment and help them manage their swelling human inventory.”

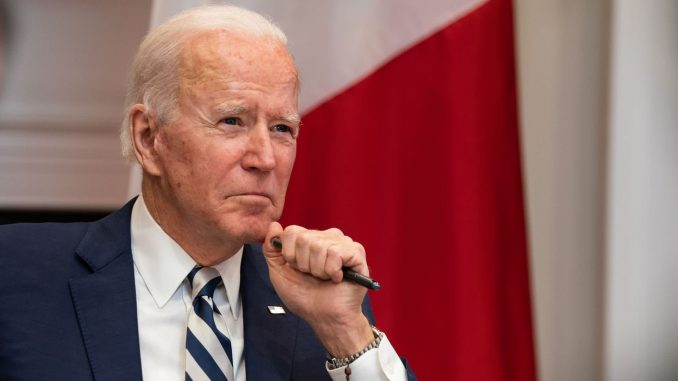

Moreover, it is likely to get even larger. Biden’s bicameral U.S. Citizenship Act will bring migrants from all over the world who think they may be able to participate in its legalization programs.

This isn’t just a border crisis. A surge of this magnitude during a deadly pandemic is a health crisis too. According to the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Dashboard, COVID-19 has claimed the lives of more than 500,000 people in the United States.

CBP has had 8,017 confirmed COVID-19 cases.

On Feb. 18, 2021, Rep. Linda Sanchez (D-Calif.) and Sen. Bob Menendez (D-N.J.) introduced Biden’s immigration bill.

Here are a few of its most troublesome provisions —

New terminology

The bill would replace the term “alien” in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) with the term “noncitizen.”

According to UC Davis professor Kevin Johnson, the use of the term “alien” helps to reinforce and strengthen nativist sentiment toward new immigrant groups, which in turn influences responses to immigration and human rights issues.

He may be right, but should Congress be changing the terms in the INA to ensure that our immigration laws are properly influencing the way people think?

George Orwell in his book, 1984, called it “newspeak,” — a new language characterized by the elimination or alteration of certain words for political purposes.

Is Biden taking us in that direction with his substitution of “noncitizen” for “alien”?

‘Lawful Prospective Immigrant’ status

Section 1101 of the bill would provide lawful prospective immigrant status for undocumented aliens, which would lead to eligibility for lawful permanent resident status (LPR) in five years.

This is controversial for a number of reasons. The one that concerns me most is the fact that no one knows how many undocumented aliens there are in the United States.

DHS, the Pew Research Center, and the Center for Migration Studies all use a process known as the “residual method” to estimate the undocumented alien population. This involves making an estimate of the number of foreign-born people in the United States on the basis of data from the annual American Community Surveys (ACS), then subtracting the number of lawful immigrants from the foreign-born estimate: The remainder is the estimate of the undocumented alien population.

This is not a reliable way to estimate how large the undocumented alien population is.

The ACS only questions 1 percent of the population; moreover, it asks for a person’s place of birth and whether he is a citizen of the United States. It is unrealistic to expect undocumented aliens who are trying to avoid detection to answer such questions truthfully.

Official estimates therefore are almost certainly low.

Dream Act

Section 1103 of the bill would provide legalization for aliens who were brought to the United States illegally by their parents when they were children. This is a sympathetic group. Even former President Donald Trump wanted to help them, but he wanted to end chain migration as a condition for granting them LPR status.

It may be possible to resolve this issue by creating a place for them in the Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) program instead of enacting a DREAM Act.

American Promise Act

Section 1104 of the bill would provide LPR status for aliens who have been in the U.S. since Jan. 1, 2017, and had or were eligible for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) or Deferred Enforced Departure (DED).

I don’t understand why Biden included a TPS legalization provision in his bill. A single Republican can prevent a bill with a TPS legalization program from being considered in the Senate with a point of order objection pointing out that it violates the TPS statutory provision, INA §1254a(h). That provision requires an affirmative vote of three-fifths of the Senate to consider a bill that provides lawful temporary or permanent resident alien status for any alien who has TPS status — or that has the effect of amending or limiting the application of this subsection.

Agricultural Workers Adjustment Act

Section 1105 of the Biden bill would provide LPR status to aliens who have performed agricultural labor or services for at least 400 days in the five-year period immediately preceding the date on which they file their application.

Farm worker programs have experienced serious problems.

The U.S. agricultural industry has relied on immigrant labor for decades, dating back to the Bracero Program in the 1940s that allowed millions of Mexicans to come to the U.S. as farmworkers. The Bracero program was ended in 1964, in part because many of the workers faced low wages, horrible living and working conditions, and discrimination. The program also created a large pool of cheap labor that held down farm wages for American workers.

The 1986 Special Agricultural Worker (SAW) program did not work out well either. It has been called “perhaps the largest immigration fraud ever perpetrated on the U.S. government.”

It may not be long before there is an outcry for Biden to reverse his immigration policies and withdraw his immigration bill if the surge in illegal immigration continues.

According to the Rasmussen Reports, 71 percent of the Republicans and 63 percent of the unaffiliated voters already think his administration isn’t doing enough to reduce illegal border crossings and visitor overstays, as do 34 percent of Democrats.

Nolan Rappaport was detailed to the House Judiciary Committee as an executive branch immigration law expert for three years. He subsequently served as an immigration counsel for the Subcommittee on Immigration, Border Security and Claims for four years. Prior to working on the Judiciary Committee, he wrote decisions for the Board of Immigration Appeals for 20 years. Follow his blog at https://nolanrappaport.blogspot.com.

Via The Hill