Amid the fire and fury of Rudy Giuliani’s raucous, 90-minute press conference Thursday laying out President Trump’s claims of widespread voter fraud, the former New York City mayor and federal prosecutor famous for busting the mob in the 1980s, declined to offer an opinion on one very substantive question: Does he think the American election system is so rigged and Trump supporters are so mistrustful of the election process that federal authorities should monitor the two Georgia Senate runoffs set for Jan. 5?

“I can’t say what’s going to be done about it. … I really can’t give you an opinion on that,” Giuliani told a reporter when the freewheeling, opinion-filled presser shifted to questions from the media.

“I think every election should learn something from this and be very, very careful with the next election.”

The reporter who shot the first question at Giuliani brought up Operation Greylord, an investigation conducted by the FBI, the IRS’ criminal division, the U.S. Postal Service and the Chicago police that rooted out court corruption in Cook County, Ill., in the 1980s.

The three-year undercover operation resulted in the indictments of 92 judges and other officials, most of whom were convicted. The trials extended over 10 years.

Even though it was a friendly question, Giuliani didn’t want to go there.

“I have no idea where the FBI had been for the last four years,” he remarked.

“…I don’t know what we have to do to get the FBI to wake up. Maybe we need a new agency to protect us. I have no idea.”

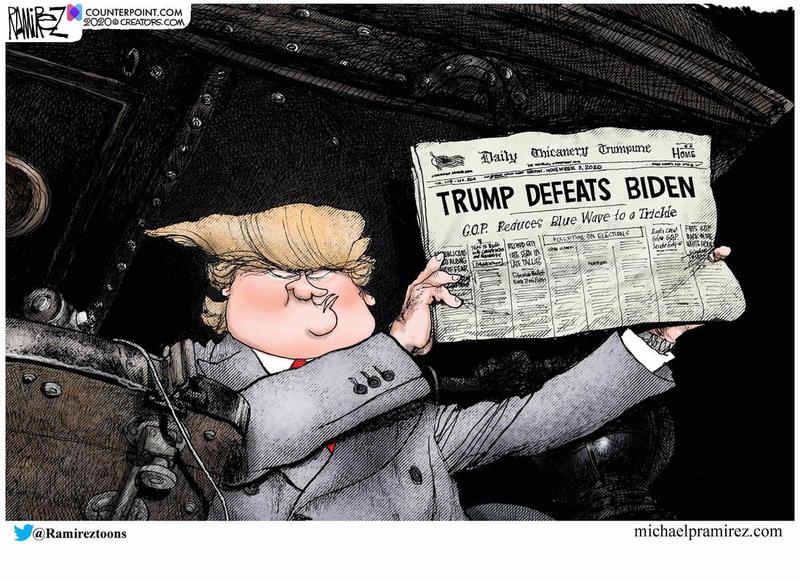

No matter what you think of Giuliani’s defiant press conference and Donald Trump’s refusal to concede, trust in the U.S. election system among nearly half of the nation who voted for the president is hitting new lows.

A Morning Consult survey released this week found the share of Republicans who trust official election results has dropped by 43 percentage points. In a poll conducted in late October, 70% of Republicans said official election results will be either “very” or “most likely” reliable. In the post-Nov. 3 survey, just 27% say the same, with two-thirds of Republicans saying the 2020 election was not free and fair.

Giuliani and others assert that widespread fraud is what shifted Georgia to the Democrats in the presidential race, not the changing demographics of the state and Stacey Abrams’ much-touted voter-registration and turnout drives. Fueled by an army of well-founded liberal groups, Abrams groups registered 800,000 Georgians to vote this year.

Georgia completed its by-hand recount of 5 million ballots Thursday, and — despite uncovering 6,000 ballots overlooked in the initial process — it validated the initial outcome: Joe Biden won the state by more than 10,000 votes. Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (pictured) plans to certify the results later Friday.

With Senate control hanging in the balance, cash from deep-pocketed special interest groups is flooding into the Peach State – some $125 million over the last two weeks — and an army of activists from across the political spectrum have arrived to organize and orchestrate highly targeted turnout efforts. The race is now on to get 23,000 of the state’s 17-year-olds — those who will turn 18 before Jan. 5 — to register to vote by the Dec. 7 deadline, using Twitch streams, mobile gaming spots and online algorithm-targeted ads.

So much is riding on the two runoffs pitting GOP Sens. David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler against, respectively, Democratic challengers Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock, that failed Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang and columnist Tom Friedman encouraged Democrats to move to the state temporarily and register to vote.

The pair have since backtracked, arguing their remarks were flippant and meant to underscore the contest’s high stakes. Still, some wealthy California Democrats are reportedly traveling to Georgia to boost turnout operations and do whatever is necessary to help Democrats win the seats.

Whether outside parties flocking there could backfire on Democrats by fueling parochial pride is an open question, but Republicans are on high alert. Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr last week warned that moving to the state temporarily to vote is a felony offense that carries a 10-year prison sentence and a maximum $100,000 fine.

“You can’t be a canvasser for [Michael] Bloomberg – you can’t be a canvasser for the Koch brothers and decide, ‘Hey, I’m going to vote while I’m here,’” Gabriel Sterling, a Georgia election official, said last week.

Though Yang insists it was obvious he was joking, conservatives deeply concerned about election fraud aren’t laughing.

Hans von Spakovsky, an election law expert at the Heritage Foundation who has advocated for stricter voting laws, is urging Georgia Republicans to implement a detailed plan before the runoff to combat several types of potential voter fraud.

Republican officials should comb through voter registration lists and divide them up by voters in each precinct, he told RealClearPolitics. Every polling location has a local monitoring committee, he explained, and each chairman should get the list of voters for that precinct. Voter registration lists can then be checked against the DMV’s list of residents and other state record databases.

“I would distribute the list and say, ‘Look at everybody in your neighborhood who goes to that polling place — are there people on it that are not part of your community?’ Go over the list and check addresses” and ask neighbors if people recently moved there, he said.

“If there’s a single family home in your neighborhood, and there’s 20 people registered there, okay, that’s a problem,” he said.

“They should immediately bring that to the attention of local officials. That’s what they ought to be doing now.”

But the No. 1 priority for combating voting fraud — or even the perception of it — should be to have poll workers, not just poll watchers, actually opening and counting mail-in ballots, providing eyes and ears on the ground, he argued.

Von Spakovsky, who worked on behalf of Republicans in the 2000 Florida Bush-Gore recount, said Republicans must demand more transparency. He cited media reports that only one observer per 10 tables of vote counting was allowed during the Georgia recount because of COVID-19 social distancing rules.

“Whoa, what is going on with that?” he asked. “There ought to be an observer at every single table where the recount is occurring. That’s what they did in Florida. I know. I was there.”

Heritage Action, the Heritage Foundation’s political arm, says it’s mobilizing 20,000 of its local members in Georgia for door-knocking, phone calls and texts. It’s also recruiting a team of at least 100 poll workers to watch for any attempts to manipulate election results. Jenny Beth Martin, president of the Tea Party Patriots Citizens Fund, said her group plans to train poll workers and poll watchers on what to look for. “We will be engaging in precinct operations,” she told RCP.

All of these efforts take manpower, and Republicans are privately fretting that the GOP didn’t do enough to prevent the runoff by countering Abrams’ extensive grassroots activities. As Giuliani signaled, they also don’t trust the FBI or other federal authorities to do anything to guard against or investigate fraud if there’s evidence of it occurring.

John Yoo, a conservative lawyer who worked in the George W. Bush Justice administration, says Trump’s concerns about expanded mail-in voting leading to more opportunities for voter fraud are well-founded. President Jimmy Carter and James A. Baker III, secretary of state under George H.W. Bush, came to the same conclusion in 2005 after heading the Commission on Federal Election Reform, which concluded that “absentee ballots remain the largest source of potential voter fraud.”

The practice of targeting senior citizen nursing homes and hospitals and helping elderly voters fill out their ballots is such a common practice that there’s a name for it among political operatives – “granny farming.” During the pandemic, there has been new concern about disenfranchising elderly people’s right to vote because of older Americans’ reluctance to go to the polls. But that fear has been abused, Yoo asserted.

Critics of ballot harvesting, or the third-party collection of mail-in ballots, often refer to an incident uncovered by the Miami Herald in 1998 in which a 70-year-old woman recovering from a stroke complained about being badgered for her absentee ballot by a political operative who then filled it out and took it from her.

“What everyone should be concerned about is if we see suspicious levels of voting – more votes than residents – at nursing homes or group homes,” Yoo said. He skeptical, however, that a significant number of people have moved illegally to vote.

Instead, he says the two areas of greatest concern are ballot harvesting and the tabulation or accounting process of all ballots.

Trump’s legal team has taken aim at the electronic voting tabulation process and the Dominion Voting System machines involved. Sidney Powell, one of Trump’s lawyers, insists that the president won by “millions of votes” and that the Dominion software altered the tallies. She has cited an affidavit signed by a former military official from Venezuela that the system was used to electronically flip votes for strongmen Hugo Chavez and his successor, Nicolas Maduro.

The state of Georgia uses Dominion machines and software, but Raffensberger, the secretary of state, said an audit of those machines found no signs of foul play.

And Jason Snead, the executive director of the conservative Honest Elections Project, says that Trump’s legal team has yet to provide enough evidence of widespread fraud for him to believe Dominion altered or tampered with “millions of votes or anything along those lines.”

“There are clearly issues that happened on Election Day, and some of them have been well documented,” he said. “Some counties in a few states had problems with some equipment, but nothing that was really outside the norm for these sorts of systems.”

Snead said those making election laws have the responsibility to ensure that they’re managing the demand for increased mail-in voting options during COVID in a way “that will ensure that those ballots are properly protected and that the election system as whole runs smoothly, efficiently and securely.”

One of the problems is that election fraud is hard to prove, and local district attorneys have shown little appetite for prosecuting it. Such cases take a lot of time to investigate, and state legislatures haven’t made the issue a funding priority, von Spakovsky and others say.

In 2018 Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich launched an election integrity unit to “preserve public confidence in the integrity of our elections by vigilantly defending ballot safeguards and common-sense voting laws.”

On Tuesday Brnovich publicly called on critics of the election process to come forward with “facts and evidence” so his office can investigate.

After an election that has fueled so much distrust in the system, von Spakosvksy is urging all states to create similar election integrity units in their attorney general offices and for legislatures to provide enough resources for those units to do a thorough job.

Snead said Brnovich is pursuing a “blockbuster” ballot harvesting case dealing with two provisions of Arizona law that the Supreme Court has said it would review this fall. One aspect deals with state laws requiring people to vote at their specific precinct and another to restrict ballot harvesting, limiting who can collect and deliver a person’s ballot to a family member, household member or caregiver.

Depending on how the high court rules, more restrictive voting laws in several states could be on the chopping block — or enshrined as needed safeguards.

“So this is going to be a big, big case,” he said. “It has the potential to help define and shape election law going forward.”