The disconnect stems from the media’s insistence on exploiting the interplay between the self-avowed nonpartisan intelligence community and policymakers.

Politico published a piece last week titled, “Biden would revamp fraying intel community,” which quoted former Obama-administration intelligence officials and Biden-campaign surrogates making the case that a Biden administration would restore “morale inside the agencies, legitimacy on Capitol Hill and public trust in the intelligence community’s leadership.”

Several interview subjects warned that part of the problem lies with the deference that current intel officials show to a president who is profoundly uninterested in the product of intelligence gathering when it doesn’t further his political ends. The former intel officials juxtaposed that stance against President Obama’s supposedly apolitical curiosity.

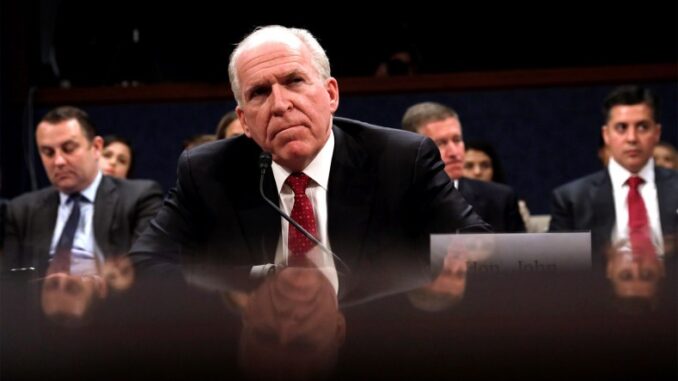

“We knew we’d be the skunk at the party because we would be presenting intelligence that might be at odds with the prevailing view,” John Brennan said of his past briefings as former CIA director. “I was questioned on it, challenged on it, and rightly so. But I never felt that they didn’t want to hear it.”

CIA director Gina Haspel is singled out as a culprit of the allegedly deferential culture. “Gina is a good woman, but she would have to go,” said former CIA and NSA director general Michael Hayden.

But on Sunday, Axios cited two anonymous Trump advisers who said that Trump also plans to replace Haspel, along with others, because he doesn’t trust them. (CBS’s Catherine Herridge confirmed the report on Monday.)

“The view of Haspel in the West Wing is that she still sees her job as manipulating people and outcomes, the way she must have when she was working assets in the field,” one unnamed adviser said.

The fact that sources in both the Biden and Trump camps view Haspel — a career CIA official — as an obstacle perhaps says more about the political climate than about the intel community itself. And while some in the media may be happy to cast the 2020 election as a binary choice between one administration that would depoliticize the intel community and another that would further harm its credibility, ex-officials claim such a diagnosis ignores history.

“It’s been there ever since 1947,” former CIA station chief Daniel Hoffman said of politics impacting the intelligence community. He pointed to examples in all three of the last administrations: the recent decision by Trump’s director of national intelligence John Ratcliffe to release raw intelligence about the origins of the Trump-Russia probe, the Obama administration’s Middle East policies regarding Syria and Iran, and the Bush administration’s treatment of the Iraq War.

“They all do it, is my point, and they’re all critical of each other for doing it, but it’s an age-old kind of bad practice,” he continued, dismissing the notion that the future credibility of the intel community hinges on the outcome of the election.

Former officials who spoke to National Review said that much of the politicization stems from the media’s insistence on exploiting the interplay between the self-avowed nonpartisan intelligence community and policymakers to drive predetermined narratives. In an effort to wrap themselves in the credibility of the intel community, reporters and columnists will often lean on former officials to provide analysis of current events based on incomplete information.

“Journalism should maintain the same tradecraft standards used by the IC,” former senior CIA official Norman Roule said. “This is to ask exactly how someone — who may have left the IC years ago or held only a mid-level position in a bureaucracy — can speak with such confidence on compartmented issues of the day.”

“Just because someone worked in the intelligence community doesn’t mean they needed to see all the information available on an issue” to be able to make an informed comment, he continued. But in cases where the media is intent on a flashy, top-line takeaway, “an individual may believe he or she had the full story, when all they received was that portion of information needed to conduct their work.”

David Shedd, former acting director of the Defense Intelligence Agency under Obama, echoed Roule’s assessment.

“The role of former IC leaders playing the role of political pundits in the current environment is extremely damaging,” he told National Review. “It goes both ways, by the way, it could be on the right, it could be on the left, I’m just saying generically. But it messages that, you once held a position of high status — in my case, it would’ve been acting director of DIA — and now you’re in some armchair opining on all sorts of things that are outside of the remit. And even when they’re in the intelligence domain in terms of knowledge, they’re talking about things either they don’t have current access to, or they’ve politicized it.”

Last week, over 50 former intelligence officials — some of whom were also quoted in the aforementioned Politico article — wrote a letter arguing that the recent Hunter Biden laptop story “has all the classic earmarks of a Russian information operation.”

“We want to emphasize that we do not know if the emails, provided to the New York Post by President Trump’s personal attorney Rudy Giuliani, are genuine or not and that we do not have evidence of Russian involvement,” it reads. But, it continues, “there are a number of factors that make us suspicious of Russian involvement.”

Hoffman said he was approached to sign the letter, but decided against it.

“I read it, and I thought, ‘There’s too much speculation,’” he explained, adding that he didn’t necessarily disagree with those who wrote or signed it. “To me, we needed more context, more facts before making a judgment about whether Russian intelligence was behind it. Piecemeal release of information, which skips the step of having the IC analyze what it means, just allows the issue to be used as more fodder in our hyper partisan debates — just like Ratcliffe.”

“That’s not what we should do. The intelligence community will give you analysis, based on all source intelligence,” he continued. “So you don’t just look at one report in particular, it’s everything all put together. And then you get a really good analytical product with those levels of low, medium, or high confidence.”

Center for Security Policy CEO and CIA veteran Fred Fleitz said that the letter and its lack of concrete evidence serves the interests of the media, not the intelligence community, and also furthers the Republican talking point that intelligence officials are out to get the current president, making “it harder to convince Trump and other Republicans that the intelligence community is of any value.”

“It has great value,” he said. “But how do you convince Trump with that now, after letters like this?”

Fleitz also lamented the way in which the media so often presents intelligence reports as either true or false, rather than as an informed opinion that doesn’t necessarily bind the president to any particular course of action.

“What is intelligence analysis — is it truth? No, it’s opinion,” he explained. “It is usually the best opinion around, it may be truthful, but the president is not obligated to follow the opinion of the intelligence community.”

By presenting intelligence reports as unimpeachable documents which require a prescribed policy response, the media conflates the role of politicians with that of intel officials, Shedd explained.

“The job of that intelligence professional is not to say, ‘Mr. President, or Mr. Secretary of Defense, or State, or Homeland Security, do this, this, and this, and all will be well if you make that choice,’” he said. “Rather, it’s for the policymaker to say, ‘if I do x, what will the reaction be, in the context of what we’re talking about notionally, of that adversary. How will they respond to it?’”

Hoffman pointed to the Obama administration’s successful takeout of Osama bin Laden as a good case of the dynamic.

“There was no 100 percent level of confidence he was there, because we didn’t confirm his presence. The president’s got to make a call, like he did on so many other occasions, with imperfect information,” he explained. “I think politics may have played a role in that too, and that’s fine, we all get that. What if the nation knew the president had a 50–50 shot of killing bin Laden and he didn’t take it? That’s politics, and it’s separate — entirely separate — from what we intelligence officers do, which is delivering the all-source analysis. What the president does with it, and the reasons for his decision — which extend beyond the intelligence he reads — is up to him.”

In other words, intelligence requires context — and stripped of important nuance and points of disagreement, it can be weaponized. Take the “bombshell” Russian bounties story broken this past summer by the New York Times, for example.

After anonymous officials leaked assessments of a Russian bounty program that allegedly rewarded the Taliban for killing U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan, the media flooded the airwaves with questions about why the Trump administration had not acted, despite the intel’s presence in the president’s daily brief. The assumption? The authentic intel was “true.”

Much of the subsequent coverage turned into partisan attacks, amplified by a media trope that Trump’s “affinity” for Putin compromises his ability to govern. “Dissonance between Trump and administration officials over Russia disguises lack of strategic approach to Moscow,” an August headline in the Washington Post read. Joe Biden used the bounties story to argue that “not even American troops can feel safer under Trump,” while Trump complained the story was “fake news.”

But the reality is that the IC didn’t agree on the intelligence, even as the media reported on it and both political sides treated it as done-and-dusted. By the time things settled down, General Frank McKenzie — commander of the U.S. Central Command in Afghanistan — revealed in September that “it just has not been proved to a level of certainty that satisfies me.”

“We continue to look for that evidence. I just haven’t seen it yet,” he said.

Roule declined to comment on the bounty story specifically, and said it was “a valid question” for the media to focus on how policymakers respond to streams of intelligence. But he stipulated that the media’s insistence on covering intel stories from a purely political angle inevitably results in oversimplification and obscurantism.

“In those instances when a leak concerns alleged alarming information, we should also ask why the many smart and patriotic professionals in this collective body didn’t respond to the data,” he said. “Perhaps the information may not have been exactly what the story describes, or relevant policy makers initiated what they believed to be appropriate counter measures.”

Via National Review