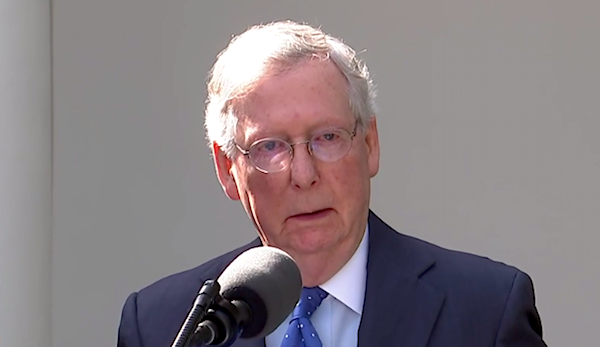

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.

Despite the president’s continued protests, it’s clear that president-elect Biden will be the next occupant of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. And even with a surprisingly dismal election performance for the Democrats, in both state races and congressional contests, they retained a slender majority in the U.S. House. Still up in the air, however, is control of the U.S. Senate. On that count, all eyes are on Georgia, where twin January 5th runoff contests will determine the balance of power.

There are two notable outcomes from the Georgia contests between GOP incumbents David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler and their respective challengers, Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff. The first is that Democrats win both seats and claim a 50-50 Senate. The second is that Republicans win one or both seats, in which case Biden would be the first newly elected president in decades to face a Senate controlled by the opposition.

If Democrats sweep both seats, they’d control the 50-50 Senate on the basis of vice president-elect Kamala Harris’s tie-breaking vote, and would enjoy (although by a wafer-thin margin) unified controlled of Washington. The complication for Democratic Senate leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) is that such a scenario would make the rightmost Democratic senator, West Virginia’s Joe Manchin, perhaps the most important person in the nation’s capital. The Democrats would only be able to go as far and as fast as Manchin would allow.

Given that Manchin has indicated he would reject calls to abolish the legislative filibuster, even a Democratic Senate would need GOP votes to enact major legislation — or would have to rely on reconciliation, in which case only provisions that directly impact taxes or spending are permitted. And, even if he leaned on reconciliation, as Republicans did to enact their 2017 tax bill, Schumer couldn’t afford even a single Democratic defection. Once again, this means that even reconciliation-fueled lawmaking could only move forward with Manchin’s acquiescence.

For education, this means that, even under the Democrats’ best-case scenario, ambitious legislative proposals like free college or federal directives to aid union organizing are dead on arrival. Any major education legislation that includes anything more than dollars and cents would require Biden and Schumer negotiating with Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY). Of course, both Biden and McConnell are consummate pros with a relationship that spans decades, so such negotiations could potentially yield surprising bipartisan agreements. For instance, when it comes to something like increasing Pell Grants or adding federal funds for special education, it’s not hard to see the contours of an agreement — especially if Democrats agree to emphasize mechanisms which steer aid to individuals rather than institutions.

But, between Democrats’ frail House majority, Manchin proclaiming that he’ll protect the filibuster, the limits of reconciliation, and the need to win GOP votes to move major legislation, even a surprisingly good night for Democrats on January 5th will have a less profound impact than many might imagine.

On the one hand, a Democratic Senate would make it a lot easier for Democrats to push large spending increases. Even the moderate wing of the Democratic party is going to be supportive of expansive COVID-19 relief, new funds for state and local government, and more dollars for K-12, higher education, and early childhood. Using reconciliation, Schumer would be able to move much of this without a single Republican vote, and a narrow Democratic majority in the House is likely to stick together on such efforts.

On the other hand, much of what has excited progressives this year has extended beyond spending to things like “free” college, federal debt forgiveness, federal protections for union organizing, and new federal legislation governing gender identity in educational settings. This is stuff that can’t be pursued via reconciliation and that is not going anywhere so long as the filibuster remains intact.

Of course, the betting odds are that Democrats won’t claim both Georgia seats. If it’s a GOP Senate, everything will turn on the relationship between McConnell and president-elect Biden, and on how far the Biden administration opts to move via executive action. There will be an interesting dynamic at work here. Biden may throttle back on executive action if it’s expected to yield more legislative success with McConnell, as more aggressive executive action is sure to create tensions with Hill Republicans. How the administration weighs the cost-benefit here, or even whether a Biden White House is able or willing to rein in activist cabinet agencies, is something that only time will tell.

This is what makes the current student loan forgiveness brouhaha so potentially illuminating. The progressive base wants the president-elect to signal that he’ll assert sweeping executive authority to forgive as much as $1.5 trillion in federal student loans in an unprecedented move. If Biden attempts this, it’ll poison any conversation with Republicans about higher education. If he doesn’t, it will frustrate and disappoint a chunk of the activist left. How the Biden administration seeks to negotiate such tensions will help determine what the next few years hold for American education.

Frederick M. Hess is the director of education policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute. Hannah Warren is a research associate at AEI.